Uncommon Media (December 2018, updated June 2022, July 2024)

June 2022: The sections Mini-Cassettes and Microcassettes have been expanded.

July 2024: The section Nitrocellulose Lacquer (“Acetate”) Records has been revised and expanded, and the sections More 78 Record Variants and Vertical-Cut 78 Records have been added

As I was developing the operations concept for my audio conversion business, I envisioned addressing media that historically had been in the mainstream: 78s, 45 and 33 1/3 rpm microgroove records, and Compact Cassettes (the formal name for what is generally referred to as “cassette”). I added reel-to-reel tapes simply because I had a tape deck. With these media in mind, I purchased, upgraded, or reconditioned equipment to handle these needs.

While most of my projects have been what I expected, customers sometimes surprise me with recordings on media I hadn’t planned on. These are presented below, and I will update this article as I encounter more uncommon sources.

Uncommon Media I Have Converted

Nitrocellulose Lacquer (“Acetate”) Records

While most commercial 78s were made of shellac resin, records were also made from lacquer, plasticized with castor oil and applied to aluminum, glass, or cardboard cores. Introduced in 1934, they were designed for direct-to-disc recording where sound was cut onto a blank record that would become the finished product (see Figures 1 and 2; the additional hole or holes were to anchor blanks on the cutting lathe so the records wouldn’t slip during cutting).

Figure 1: Lacquer disc transcription of a concert recorded on magnetic tape (12”, three anchor holes).

Figure 2. Lacquer disc intended for home recording (7”, one anchor hole)

Lacquer records are frequently referred to as “acetate” records, but there is no acetate in their composition. The term appears to be attributable to a warning on some labels to “Use only acetate needles” to play these records, which refers to high-grade steel needles that wouldn’t degrade the lacquer as rapidly as inferior needles. Physically, these records were subject to chipping, and they were more vulnerable than shellacs because the castor oil could leach out of the record (notably by using Saran Wrap to protect the record), rendering the records unplayable. Lacquer records recorded at 33 1/3 rpm were more prevalent in the 1950s, allowing about 11 minutes per side. Regardless of speed, playing them on a modern turntable requires a 78 stylus.

One of their intended uses was to transcribe performances recorded on magnetic tape onto records that the artists could play at home (magnetic tape was not a readily available medium for home use until the 1960s). The record in Figure 1 is an example. Since 12” 78s would accommodate only five minutes or so of recording, longer pieces were split and transcribed onto one or more additional sides. Ideally, splits would be made at rests in the music. But if the music was continuous, splits had to be made in unexpected spots, hopefully backspacing the tape so there would be some overlap to reestablish continuity on the ensuing side. I have encountered both conditions in concatenating parts into a single, long track.

Another use was for personal recordings, and their popularity increased through the 1940s and 1950s, at which point the medium was overtaken by magnetic tape. Lacquer recordings were typically made at home or in coin-operated recording booths (see Figure 3), and the medium became especially popular during World War II for sending spoken messages between troops overseas and their families back home. Though popular for personal recording, the sound quality of lacquer records was limited by the technology of the time, comparable to that of shellac 78s.

Figure 3. RCA Victor souvenir lacquer record label from the 1940 New York Worlds [sic] Fair.

Though obsolete as finished products, nitrocellulose lacquer records with aluminum cores have been and are still used in the first step of a multi-stage process in the production of vinyl records. Using a lathe, the audio recording is cut onto a lacquer blank. The cut blank is sprayed with tin chloride and liquid silver and electroplated with nickel. The fused metal layer is then removed and serves as a stamper for pressing the vinyl records.

More 78 Record Variants

78s for Home Recordings: I recently completed a project that included numerous home recordings made on 7”, 8” and 10” blanks. Several had a solid lacquer base; others were flexible, as the one pictured in Figure 4. Irrespective of the base material, almost all of them were subject to incessant skipping, often with the tonearm skimming across the entire width of the record. I suspect this was due to a lighter cutting head than would be used on a professional cutting lathe, resulting in shallower grooves. While this wouldn’t have been an issue in the 1940s when tracking weight could be measured in ounces, shallow grooves pose a problem for my turntable tracking at the recommended weight of 1.7 grams. While I experimented with each record individually, I nearly always had to increase the tracking weight to 3.0 grams, the highest setting on my tonearm. At the same time, I had to increase the anti-skate setting to its maximum to help eliminate skipping. (The anti-skate feature applies a force that counteracts a tonearm’s inherent tendency to drift toward a record’s center.)

Figure 4. Flexible disc intended for home recording (10”, two anchor holes).

Tracking Direction: Given my and my readership’s collective experience, we expect records to begin playing at the rim and end near the label. But that’s not always the case. Some records created into the 1950s tracked from the inside out, i.e., from the label to the rim (see Figure 5 for a label where the creator could indicate tracking direction, speed, and groove cut [defined below]).

Figure 5. Label with indicators for tracking direction

(In vs. Out), speed, and cut (Vertical vs. Lateral).

A “normal” record that tracks from the rim has two aids: a raised rim that helps prevent the stylus from slipping off the record and a short run-in groove that catches the stylus before the music or other content begins to play. The records I’ve encountered that track from the label do not have a run-in groove; the stylus must catch the beginning of the music (or within one revolution of the beginning, depending on one’s luck). If the stylus doesn’t catch a groove, the geometry of the tonearm pushes the stylus further toward the center of the record, usually to the point where automatic or semi-automatic turntables lift the tonearm and stop. A second difference is that there’s no run-out groove at the rim. The final groove runs back into itself, and this self-induce skip indicates rather gracelessly that the music has reached its end.

Parenthetically, the two rings of black bars around the edge of the label in Figure 5 are to aid adjusting a turntable’s speed. When viewed under a 60 Hz fluorescent light, the stroboscopic pattern of the outer ring will be stationary at 33 1/3 rpm, and the inner ring’s pattern will be stationary at 78 rpm. (I have a similar aid that includes a third ring for 45 rpm.)

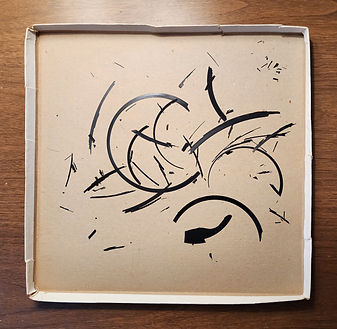

Wax Layer Applied to a Cement Base: As I was inspecting a collection of a customer’s records, I opened a flat record box and removed the sleeved record. What I spotted in the box appears in Figure 6. The black shards of what resembled thin plastic were curved, conforming to the shape of grooves on a record. When I removed the record from its sleeve, my fears were confirmed. The layer with the grooves had loosened from the base and cracked, and pieces had fallen into the sleeve and box. Figure 7 shows Side 1, which exhibited severe damage near the rim, additional damage in four spots around the rim, and damage near the label (name of artist masked). Not good!

Figure 6. Record box with shards of abraded groove layer.

Figure 7: Record with abraded groove layer (12”).

In researching the Pathé-Marconi label, I discovered that the records they manufactured in 1905 consisted of a layer of wax on a cement base, and that description is consistent with my customer’s record. Although Pathé abandoned wax-on-cement for shellac in 1906, I hypothesize that they had leftover stock of wax-on-cement blanks. My customer’s record was created in 1938 when the artist was a piano student in Paris, and Pathé may have used their old stock for what would have been at most a few copies. I was able to digitize about 2.5 minutes from Side 1 (visible in Figure 7) and about 3.5 minutes from Side 2, where most of the damage was near the label.

Mini-Cassettes

Mini-Cassettes (2.2” x 1.32” x .33”) were introduced by Philips in 1967, four years after they had introduced Compact Cassettes. The primary function was for dictation and transcription using a hand-held voice recorder (see Figure 8). Less prevalent purposes included early answering machines and data storage for a Philips home computer. The cassettes could hold 30 minutes of recording, 15 minutes on each side.

Unlike most other tape formats, the take-up reel transports the tape across the heads rather than a capstan and pinch roller. The disadvantage of this approach is that the tape speed varies, not only with how much tape has been wound onto the take-up reel, but also with the tightness and evenness of the wind. While adequate for voice recording, this technology is ill-suited for music. It does offer a distinct advantage, though. While playing a tape, the user can easily move the recorder’s slider switch from play or stop to fast-forward or rewind without disengaging the tape from the playback head. When dictating, the speaker can quickly rewind or fast-forward while listening to what was recorded (at a much higher speed, of course) and target a spot to begin recording over what isn’t wanted. The same capability aids those who are transcribing recordings to a hardcopy medium.

Mini-Cassette recorders have two other weaknesses. One is that there is no erase head. Recording over a previously used tape relies on the record head to write enough signal to mask what was already on the tape. This approach is less than perfect, and repeated re-recordings will accumulate background noise, rendering the new recording less comprehensible. The other weakness is that built-in microphones will often capture noise from the device’s tape transport mechanism.

Despite the technological limitations, there continues to be a market for Mini-Cassette recorders and their cassettes. Though expensive, both remain in production today, even in the face of competition from hand-held digital recorders (perhaps because of the easy-to-use shuttling capability, or the ease of handing a cassette to a transcriptionist rather than coordinating the transfer of an audio file).

Figure 8. Mini-Cassette (left) and Microcassette recorders with their cassettes.

Microcassettes

Microcassettes (1.97” x 1.3” x .33”) were introduced by Olympus in 1969, intended for dictation and transcription using a hand-held voice recorder (Figure 8), for answering machines (where they became dominant), and for computer storage. Microcassettes come in 10-, 15-, 30-, 60-, and 90-minute lengths (half on each side). The Microcassette recorder’s standard tape speed is 15/16” per second, half that used with Compact Cassettes. Some models offer the option of recording at 15/32” per second, which doubles the recording time—and worsens the audio fidelity. (I recently converted a 90-minute Microcassette recorded at half speed, which yielded three hours of noisy audio content.)

Olympus introduced a “high fidelity” Microcassette model in 1982 that could satisfactorily record music in stereo. This model was discontinued after only two years due to limited availability, the model’s cost, the recommended use of the more expensive Type IV (“metal”) tape, and shortened battery life (as low as two hours) because of the current necessary for the Type IV tape bias (see What Are Those Codes on Cassettes?).

Like Compact Cassettes, the transport mechanism involves a constant-speed capstan and pinch-roller, so the speed of the tape across the recording and playback heads is the same regardless of whether the tape is near its start or its end. Unlike the Mini-Cassette, the tape is disengaged from the heads when playback is stopped, and one cannot listen to the audio in fast-forward or rewind modes. As a result, shuttling forward or backward to a particular spot involves guesswork. Like Mini-Cassette recorders, Microcassette devices lack erase heads, so repeated recordings on the same tape will progressively worsen the audio quality. And the built-in microphone may capture the recorder’s tape transport noise.

Microcassette devices and cassettes are still in production and are more reasonably priced than Mini-Cassette items. I receive one or two Microcassette conversion requests per year.

Confusion Between Mini-Cassettes and Microcassettes

In my research, I’ve encountered inconsistent and often erroneous application of the terms “Mini-Cassette” and “Microcassette.” While “mini” and “micro” both imply “small,” and while both cassette types are noticeably smaller than Compact Cassettes (see Figure 9), the devices and their cassettes are not interchangeable. Mini-Cassettes are slightly larger than Microcassettes, and you’ll note in Figure 9 that the tape transport sprockets are very different.

Figure 9. Compact, Mini- and Micro Cassettes.

You would think that users and, especially, vendors would be aware of and respect the difference. Alas, this is not the case. Here are some examples of using inappropriate terms and their consequences.

-

While sellers on eBay in large part describe their Mini-Cassette devices accurately, the Item Specifics section of the posting typically lists the media as “cassettes” or “microcassettes.”It’s not clear to me that “mini-cassette” is among the choices available for that field.This can lead buyers toward making a wrong purchase decision.

-

Several one-star buyers’ reviews on eBay state that they were unable to play their own cassettes in the devices they purchased, sometimes blaming the manufacturer for a design requiring a proprietary cassette size.It’s likely that these buyers were unaware that Mini-Cassettes and Microcassettes are different, or they may have been misled as described above.

-

GE and Panasonic are selling Walkman-type devices on Amazon labeled by the companies as “Mini Cassette Recorders,” none of which specify the type of cassette used.One must read the Customer Questions & Answers section in the hopes that someone has mentioned that they use only Compact Cassettes.The likelihood that potential buyers will be misled is high, and the collection of scathing one-star reviews is richly deserved.Both companies, especially Panasonic, should know better.

-

A 2022 review of the “10 Best Mini Cassette Recorder[s]” listed seven Microcassette and three Compact Cassette devices (the GE and Panasonic models noted above), but no Mini-Cassette recorders.I find it hard to believe that the hands-on evaluation failed to reveal the two different cassette types used by these products.Given this methodological lapse, it’s fair to conclude that the self-proclaimed expert reviewers were unaware that Mini-Cassette recorders exist and that they use a third type of cassette.It’s conceivable that they may have stumbled upon the Philips Mini-Cassette recorder but dismissed it because of its price.

Instead of “let the buyer beware,” the motto to strive for should be “let the buyer be educated.”

Digital Audio Tape

Digital Audio Tape (DAT) is discussed in a separate article.

Other Uncommon Media

Vertical-Cut 78 Records

If one could see into a record’s grooves (an electron microscope would help), one would see the surfaces moving toward the groove’s center and back again. These variations impart vibrations to the stylus as it's dragged through the groove, which is the first step in getting sound out of a record. In records’ early days, there were two ways this was accomplished. In the first, invented by Thomas Edison and used for wax cylinders since their 1888 debut, the bottom of the groove moved up and down while the groove’s width remained constant. This would cause the stylus to move up and down, leading to the term “vertical cut.” (If one could view the groove from the side, the groove’s up-and-down profile gave rise to the term “hill-and-dale.”) In the second, invented by Emile Berliner, the groove depth remained constant while the sides of the grooves moved in and out. This caused the stylus to move sideways, leading to the term “lateral cut.”

Despite the precedence of vertical cutting and its use by two major (Edison Disc and Pathé) and several small record companies, lateral-cut records overtook vertical-cut ones in the marketplace, due at least in part to the use of inexpensive steel needles for lateral-cut records. Vertical-cut records required diamond (Edison) or spherical-tip sapphire (Pathé) styli for those records. Record players were designed to handle only one type of cut, though some designed for lateral-cut records could be augmented by an attachment to play vertical-cut records—at additional cost. Breadth of music selection on lateral-cut records may also have played a role. Regardless, consumers gravitated toward lateral-cut records, and like VHS sales dominating that of Betamax, production of vertical-cut records became less profitable. Pathé abandoned vertical-cut records outside of France in 1925 (still sold in France until 1932); Edison abandoned them entirely in 1927.

I have not encountered a vertical-cut record and suspect they have almost entirely disappeared. I included this section because the company that produced the 1955 record whose label appears in Figure 5 apparently offered vertical cutting as an option, presumably for customers who still used players that could accommodate such records.

I should note that lateral and vertical cutting, though modified, are combined to create stereo records.

Aluminum Records

Aluminum discs were introduced in the late 1920s to record radio broadcasts or provide archival copies for performers or sponsors, and they were occasionally used to make recordings at home or in coin-operated booths at fairs. The use of bare aluminum discs was short-lived, being overtaken by the introduction of lacquer records, described above. Most aluminum recordings fell victim to scrap metal drives during World War II.

The grooves on aluminum records weren’t cut, but rather indented by a heavy recording head. The net result was very wide grooves in a soft medium that would be damaged by any hard stylus, including steel needles in use at the time or modern crystal styli. Owners were advised to use organic needles instead, typically a thorn or sharpened bamboo (which can still be found for sale on the Internet).

8-Track Tapes

8-track tapes appeared in 1964, offering two advantages over the then current reel-to-reel tape recorders. Users no longer had to fumble with threading the tape, and due to their looped continuous play capability, one didn’t have to remove, flip, and rethread the tape to play the rest of it. Enjoying a strong market in car stereos, 8-tracks were very successful from the mid-1960s to the late 1970s.

8-track tapes played at 3.75” per second, and like reel-to-reel, they used 1/4“ tape—though with eight tracks instead of the four on reel-to-reel tapes. Rather than having feed and take-up reels like reel-to-reel, Compact Cassette, Microcassette, and Mini-Cassette recorders, 8-tracks had a single reel. To create a continuous loop, tape was pulled from the inside of the reel at its hub, transported across the read head by a capstan and pinch roller, and then wound onto the outside of the reel at its rim. The angular velocity of the reel was dictated by the speed of the tape being played and then wound onto the reel. As each layer of tape shifted position away from the reel’s rim and toward the hub, the layer’s circumference became less and less, and the tape’s linear speed (which had to remain constant in order for the tape to be played) drifted further and further away from the reel’s angular speed. Consequently, the tape was always slipping against its neighboring layers. To prevent abrasion of the tape’s oxide layer, it was coated with a lubricant. Unfortunately, the lubricant—and eventually the oxide—could be scraped off the tape, and the residue could collect on the capstan, which would cause an uneven and increased playing speed. Because of this and several other difficulties inherent in their design, 8-tracks eventually lost popularity to Compact Cassettes, which had fewer inherent problems.

Wire Recordings

Wire recorders were introduced in 1930 for uses such as dictation, and they were used extensively by the military during World War II. They were popular for home recording from 1947 to 1952, at which time they were overtaken by tape recorders. (A wire recorder was featured in the movie Dick Tracy.)

Recordings were made by magnetizing a steel wire that was .004-.006” in diameter (a bit wider than a human hair). The best wire was made of stainless steel; lesser quality wire that didn’t use stainless steel was marketed but was subject to corrosion. Typical spools contained 7200’ of wire, and a spool was capable of recording about one hour at 24” per second. Like Mini-Cassettes, the wire was transported by the take-up spool, so the actual speed was slower at the start of the wire and faster at its end. The sound quality was decent for its intended use of capturing speech, but with a frequency range of only 200 Hz to 5 or 6 KHz, wire was inadequate for music (the normal range of human hearing is 20 Hz – 20 KHz). Unlike magnetic tape, stainless steel wire recordings have not degenerated over time. Functional wire recorders are still available, but they’re vanishing. Wire recordings will likely outlast machinery that can play them.

Like a Kid in a Candy Store

There’s a certain risk associated with encountering uncommon media, and that is a sudden desire to acquire the capability to play and convert them. Hypothetically, my audio equipment wish list would include an 8-track tape deck, a wire recorder, and a gramophone or custom-built wide stylus to play aluminum records. While the first typically has a headphone jack or line out jacks, and while a wire recorder’s speaker wire could be routed through an attenuator to create a line level output signal, recording from a gramophone would require a microphone or some other kind of transducer to convert mechanical vibrations into an electronic signal. Though I’m unlikely to pursue any of these technologies in the near future, I can still fantasize about acquiring them!

Back to Paul's Blog & Contents